Grimaud’s Crowbar

Posted by Runeslinger on February 11, 2018 · 1 Comment

A brief note of introduction before we learn how Grimaud came to meet Chekhov.

Over the past year and more a small group of friends and I have been running Triple Ace Games’ All for One: Regime Diabolique as a co-operative, co-GM’d campaign. The game, developed for the Ubiquity Roleplaying system and inspiringly written by Paul ‘Wiggy’ Wade-Williams, presents the 17th Century as a setting for horror and swashbuckling rage against dying light. With all of that musketeer action going on, both in front of and behind the metaphorical screen and the actual screens of Hangouts, you, Dear Reader, will not be surprised to learn that I have been re-reading the classics by Alexandre Dumas. The combination of Wiggy and Dumas is fantastic in several senses of the word, and returning to their words often and with intent is the best way that I know to steep myself in the dark and courageous world of All for One. It was in one of these visitations of oft-read and beloved books of a time which perhaps never was, but should have been, that I once again came face to face with a most curious passage in the sequel to The Three Musketeers, a wider-ranging work called Twenty Years After. That passage has leapt out at me each time I have read it over the course of my life, and this time was no different except for one thing. That thing, of course, was the cross-pollination of the musketeers and roleplaying games.

On Guns and Crowbars and those who would use them

In Twenty Years After, the passage in question is brief, but its effect on me has been a powerful one. In it, Grimaud, the reliable lackey of Athos is on the trail of Raoul, the ward (and accidental son) of Athos as that young worthy heads off to war for the first time. While at an inn to learn how much distance he has closed with his charge, Grimaud overhears what can only be a brutal murder from an upstairs room and leaps to lend aid, for of course – by coincidence – he knows who it is being murdered.

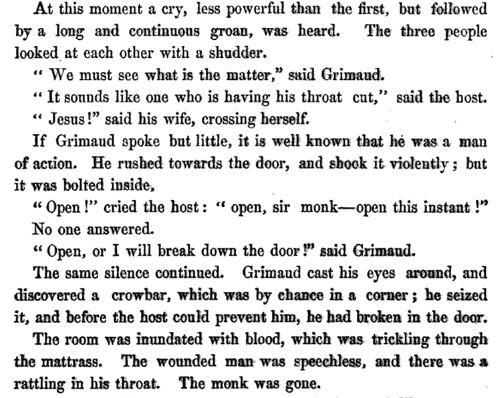

Twenty Years After, Chapter XXXIV – The Monk

How this matters, and how it connects to roleplaying games, and Anton Chekhov may seem distant now, Dear Reader, but worry not, we shall get there soon and then desist, so that you may return to events which matter more.

In a now-famous observation, Anton Chekhov, known for several things, but perhaps now most of all for his artistry as a playwright, stated that that which is not of actual use in a fictional scene should be removed. The exact observation given is that if a gun is described on the wall, it must in some way be used later in the play or removed from the play entirely. My reaction to the above passage by Dumas regarding Grimaud at the door has become a sort of corollary to Checkov’s Gun for roleplaying gamers and as you can no doubt deduce, it is called Grimaud’s Crowbar.

In short, it proposes that anything in a scene must not only be of use in the sense meant by Chekhov, it must also resonate with the tone of that scene, fit its context, and not deny action or import to other elements already established.

On how both Grimaud and this chronicler get to the point

Grimaud’s fortunate discovery of a crowbar in the hallway of the inn, with the Host and Hostess beside him, stands out for crossing over the lines of this corollary, and thereby gives it both shape and a name. For expedience and utility that authorial insertion of a fortuitous crowbar sacrifices the normal focus and elegant build toward climax for which Dumas is rightly famous, it replaces the mystery of coincidence with the vagaries of luck, and it renders several characters impotent and silent where scant lines earlier they were of vital importance. In roleplaying games, particularly those where the players have reached a specific stage of comfort in collaboration and improvisation, but not yet reached a stage of regular attunement with what is emerging in the moment to mesh with what has already been created and with each other’s additions, this same effect can manifest. What we create and insert into a scene as though it were always there, might suddenly seem to have come from nowhere, to feel out of place, and worse, might deny action to those characters or things already in place.

These little acts of creation are sometimes subtle and pass without conscious recognition by those involved in the moment. On reflection, however, they rise up in the memory of the session as a discordant element we are annoyed by or even regret. Sometimes these inventions veer away from subtlety and are so dramatic that they cause play to come to a complete halt. Going too far with whatever narrative control we have as players or as those players in the role of the GM, forgetting where the action is, and on whom and what it depends, being tone deaf to the mood and atmosphere being created around the table, and seeking to game the game for advantage can all contribute to the appearance of Grimaud’s Crowbar. It can be intentional, but is most insidious when unintentional and undetected, for then it is only visible in hindsight.

Some may say that they can escape the claw of Grimaud’s Crowbar by retreating inside the narrow footprint of RPGs with nearly-complete GM authority, but that is a sad illusion. The GM, one of the players required to play an RPG, is not immune to missteps and ill-considered additions to the world of imagination and decision that the whole group is bringing into being. Everyone has a lapse in judgement from time to time, and we only need to cast our eyes to that passage above from the master Dumas to be reminded of it. Whether our games rely on the instinct and verve of the players to give it sparks of life and solidity, or whether they rely on economies of narrative resources, or even if they are rooted in the flow of creation and collaboration through defined channels, they are each prone to spills and accidents which we – if we are mindful first of Grimaud and his lucky and ne’er to be seen again crowbar – can be more prepared to avoid, and more able to describe should we have a moment of lapsed attention.

Creation is fragile and can flower into wonder when handled with grace, skill, and care. It is not something that requires the regular services of a crowbar~

Comments

One Response to “Grimaud’s Crowbar”Trackbacks

Check out what others are saying...[…] The worst thing that can happen is occasionally the GM has to veto something as being a “Grimaud’s Crowbar” or that in this case there isn’t […]